First stop for me at this year’s Festival is Diarmaid MacCulloch’s Thomas Cromwell: a fresh look. I’m a huge fan of Hilary Mantel’s epic Wolf Hall trilogy, which miraculously breathes vivid life and motivation into Cromwell and his contemporaries. I say ‘miraculously’ but Mantel’s meticulous research is the lifeblood of her compelling fiction. Indeed, Mr MacCulloch paid tribute to his ‘good friend’ Hilary Mantel in this fascinating session.

His own obsession with Cromwell was sparked when he was an undergraduate. Retirement presented him with the opportunity to get more up-close-and-personal with this most ‘enigmatic’ man. In fact, there was so much archival material on Cromwell that Mr MacCulloch spent four years immersed in his subject researching his biography Thomas Cromwell: a life. The book is dubbed ‘a masterclass in historical detective work’ by publisher Penguin. It was exciting to hear and see the historian’s enthusiasm and delight in his subject as he led us in an illuminating analysis of pictorial evidence (Holbein portraits and heraldry) of Cromwell’s character and mindset.

Mr MacCulloch sees Cromwell as ‘looking at the world with a very fresh and original gaze. Not a typical Tudor Englishman at all’. Cromwell upped sticks as a teenager and headed for Europe – unheard of for a common or garden miller’s son from Putney. It was this travelling and his Italian connections (and fluent Italian) that gave Cromwell his foot in the court door. Cardinal Wolsey called on him to advise and project-manage the design and construction of his ornate Italianate tomb. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Although, as Mr MacCulloch engagingly explains, it’s not the history we were probably taught at school! For a more nuanced view of this intimidating and ruthless ‘fixer and bully’ who Mr MacCulloch admires for ‘being easy in his own skin’, look no further than: Thomas Cromwell: a life.

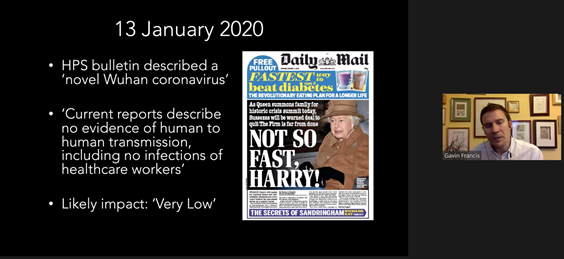

Gavin Francis, GP and writer, discussed a topic that is still history in the making: Covid-19.

Writing for Dr Francis is a way of processing being in a medical practice that is ‘thick with encounters and drama’. Although, to be honest, with his commitment to his Edinburgh practice, his locum work with the homeless in the city and seasonal locum work in Orkney, it’s difficult to understand when he gets time to write – let alone make time for his own family.

But write he does – he’s got five books under his belt equally divided between his chosen topics: medicine and travel.

His book Intensive Care: a GP, a Community & a Pandemic is his response to the last 18 months of dealing with the pandemic. ‘Covid,’ he says, ‘dominated the practice, patients and all of our lives’. Writing, he says, was a satisfying way of trying to make sense of the abstract bombardment of information and public health announcements and personalise them ‘by writing about the effect they had on my patients’.

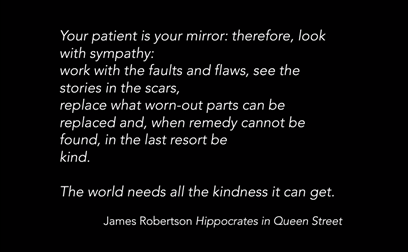

Dr Francis’ heartfelt and humane reflections on the pandemic and its impact on his patients’ physical and mental health and wellbeing as well as on communities and society as a whole make you long for him to be your GP. It was fascinating – and also depressing – to walk through the timeline and the impacts of the pandemic through the eyes of a primary healthcare worker.

However, Gavin Francis is hopeful: he’s clear that the NHS and other agencies have learnt huge and valuable lessons – in testing, in vaccination, in implementation of quarantine, accessing PPE and improving IT. He sees us as being much better prepared for future pandemics.

But he also sees the disparity in the impact of the virus on rich and poor. It’s this social inequality and its unfair impact on people’s health that he repeatedly focuses on. We need, he says, to find a way to communicate and show people that inequality is not just bad for those ‘at the bottom of the pile’ but for everyone: ‘As we emerge from this [pandemic] with better science, we need also to think about how to reorganise and restructure our health service with kindness at its heart’.

Salley Vickers’ hugely successful debut novel Miss Garnet’s Angel was published some 20 years ago. I say debut but Ms Vickers remembers writing a novel called The Door into Time when she was nine.

This, she now realises, was a sort of ‘prototype’ for many of her subsequent novels including Miss Garnet’s Angel. In the time between her early creation and that first published novel, Ms Vickers has been a special needs teacher, an English Literature lecturer, a psychoanalyst and now ‘a humble novelist’. She has a lot of life to plunder for her fiction.

However, Ms Vickers says she ‘never takes characters from life’. Even so, she acknowledges that – perhaps as a legacy of her days as a therapist – she can conjure up a lot of people or characters from her unconscious that ‘are not me but are of me’.

Time, memory and consciousness, says Ms Vickers, are not linear for individuals or generations. And, as she speaks, there’s a sense of a permeable layer that, with the right mindset, can be passed through – between fact and fiction, present and past, self and character, religion and paganism. Miracles, she says ‘happen when we look at the everyday world in a different light – they are a shift in perception’.

Ms Vickers says that her books are ‘fundamentally optimistic’. Her time as a therapist has taught her that people can come through deep trauma. What interests her, she says, is what it takes to restore the early promise we once had.

Setting and location are deeply important to the novelist – in the case of her new novel The Gardener that’s a compound of ‘various Shropshire villages’ on the Welsh Borders – steeped in Celtic Christianity and sacred wells. She drops an Albanian man into this most rural of English settings as a counterpoint to her slightly hesitant protagonist, Halcyon. ‘Plot,’ says Ms Vickers, ‘flows from character’. One of the pleasures of writing, she says, is to discover who a character is, what they will turn into and what their fate will be.

I will be heading to Grieve’s in Berwick to buy my copy of The Gardener just as soon as the delivery van pulls up.

Thomas Cromwell: a life by Diarmaid MacCulloch is published by Penguin

Intensive Care: A GP, a Community & a Pandemic by Gavin Francis is published by Profile Books

The Gardener by Salley Vickers is published by Viking 4 November 2021