Paradox was at the heart of today’s opening session: specifically, how to square faith with uncertainty. This conundrum was a constant theme in RS Thomas’ poetry. Thomas felt that ‘when conscious of God’s absence, one is aware of his presence’. Thomas died in December 2000 aged 87 and, according to our speaker Barry Morgan, ‘narrowly missed out on the Nobel poetry prize in 1995’. It was won by Seamus Heaney.

This fascinating session was steeped in the existential questions that trouble people of faith – and many of no faith.

RS Thomas did not get bogged down in theology in his poetry but thought of poems as ‘arriving at the intellect by way of the heart’. Which might, for some, apply equally to faith. Theology, says Barry Morgan is ‘systematic and tidy’ which is ‘not how poetry works’.

Rather, RS Thomas subscribed to the idea expressed by Emily Dickinson that the ‘poet tells the truth but tells it slant’. Mr Morgan says that for Thomas ‘the attempt to define him [God] is when we get into trouble’. Thomas preferred to think of understanding God in terms of ‘waves on the shore’ – always coming close and then receding – and believed that the only response to God’s ‘beyondness’ is to be silent.

Mr Morgan also introduced us to the paradoxes of Thomas himself. He was a staunch Welsh nationalist who was furious with his mother for not teaching him Welsh (he subsequently learnt the language at the age of 30). He was a caring and rigorous parish priest who hated the English tourists his parishioners relied upon for income – even advocating the burning of English-owned homes at one point.

Perhaps RS Thomas’ ability to address the profound questions of life, death and faith so eloquently and beautifully in his poetry stemmed not just from his Christianity but also from his powerful sense of being a fallible human. If you have not read any of his poetry, I strongly urge you to do so.

On to Polish double agent Michael Goleniewski: ‘the best spy the West ever had and then lost’. Tim Tate’s talk revealed another in-depth search – some may say that Mr Tate’s search provided more tangible outcomes than that of RS Thomas.

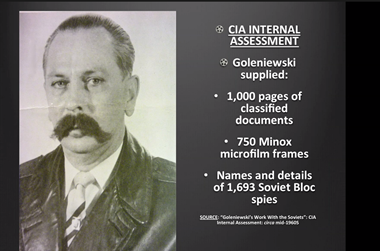

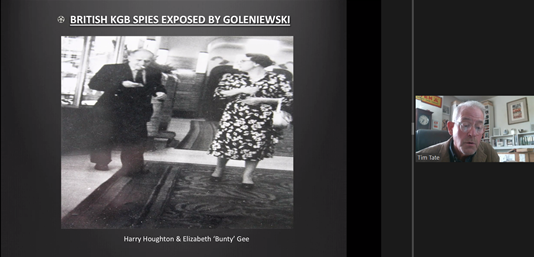

Mr Tate devoted years to piecing together the reasons why super spy Michael Goleniewski – who delivered vast and invaluable information to the CIA and MI5 about the infiltration of Western agencies and government by Soviet spies – was ‘erased from history books and airbrushed from the story of the Cold War’.

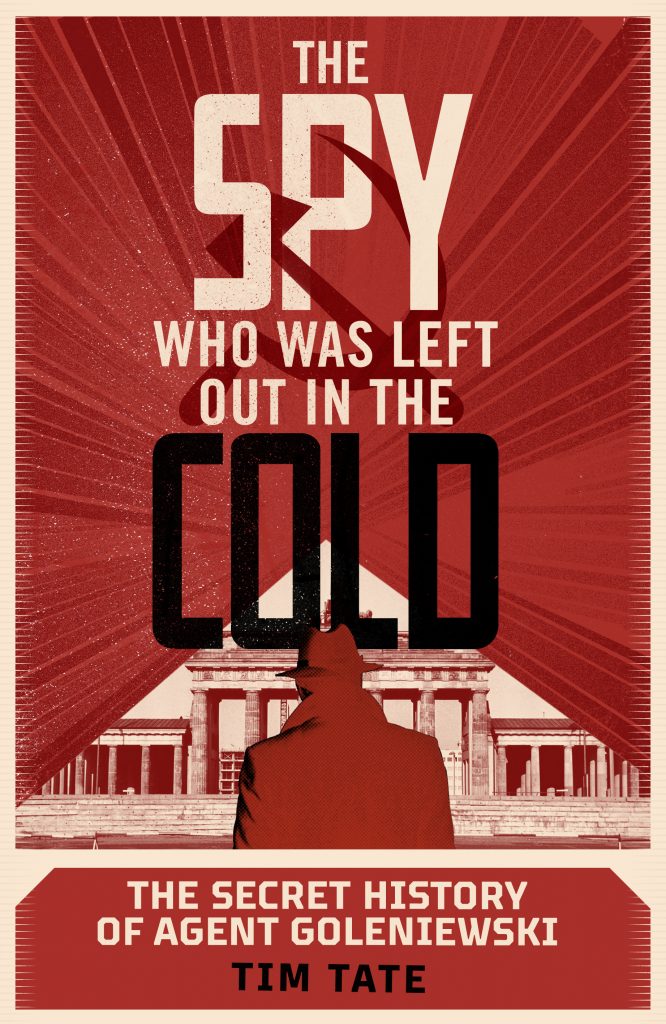

Mr Tate tracked down long forgotten and ‘suppressed’ archives across the the UK, America, Poland and the rest of Europe, piecing together an extraordinary timeline to create his book The Spy Who Was Left Out In The Cold: The Secret History of Agent Goleniewski.

Mr Tate’s timeline proved to be the key to establishing why and how the CIA, having lauded the brave Goleniewski, chose to discredit him. Ultimately they drove him mad.

Listening to Mr Tate taking us through the evidence, information and stories he’s amassed is a bit like sitting in on the most focused police procedural drama ever. He’s uncovered, as you’d expect, a web of deceit and double-dealing (mostly by the CIA), a rival defector and many curve balls – including Goleniewski’s bigamy and his bizarre (and ‘completely unfounded’ claim) to be Alexi Romanoff, heir to the Russian imperial throne. In short, he’s pieced together the most fascinating story of one man, the Cold War and its global players.

He also has a theory that these events in the 60s and 70s were key factors in paving the way for Russian intelligence interference in the US election of 2016 and ‘allegedly’ in Brexit.

Mr Tate was keen to dispel the myth of the Bond-esque spy. Spying, he says is ‘grubby, dangerous, shabby, dark and miserable’ – more akin to the worlds created by John Le Carré and Len Deighton than Ian Fleming.

Former prime minister Gordon Brown is on a quest of a different kind. He wants a ‘healthier, greener, fairer and safer world’. He sees finding ‘global solutions to global problems’ as being the key to this.

Mr Brown galloped us through a wide-ranging view of the world and the dangers of the current trend towards the creation of national silos. Wall-building (there are 65 physical walls built along national lines, half of them since the Berlin Wall came down), he says, hampers the international and community co-operation that is central to addressing the key challenges that face us all – from climate change to the impact of tax havens and from global poverty to nuclear proliferation.

Mr Brown used the financial crash of 2009 (when he was PM) and Covid-19 as case studies of how global powers can work together to problem solve, help each other and, in particular support the most vulnerable countries. He cited the sharing of knowledge and expertise in vaccine development during the pandemic. But he castigated governments for not capitalising on this by getting stockpiled vaccines to the countries that need them and instead following selfish agendas at potentially great human cost.

The financial crash, he says, showed him that it was not difficult for global heads to come together and action rapid delivery of economic support or, in this case, supplies of vaccine where they are needed. In fact, for developed countries to help less developed countries is in the former’s own interest. If we don’t address the dearth of vaccinations in less well-off countries, he says, the virus will be back to bite us in different mutations.

He also highlighted the development of the International Space Station which sprang out of the seemingly insurmountable national competitiveness that was the Cold War Space Race between Russia and America. He retold a story of an exchange between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev. Reagan is reported to have asked Gorbachev if he’d come to America’s rescue if it was subject to an ‘out-of-space attack’. Gorbachev’s reply? ‘No doubt’ and Reagan’s response: ‘We too’.

Despite the current recalcitrance towards global co-operation, Mr Brown is optimistic. More than once he says ‘people don’t co-operate out of human need but out of a human need to co-operate’. He also recasts several times the idea of ‘others’ being ‘those we need to work with rather than as our enemies’.

As you’d expect from a former prime minister, Mr Brown’s talk was peppered with salutary quotes and anecdotes ranging from JF Kennedy to Orwell, from Martin Luther King to Solzhenitsyn and from Bill Clinton to John Maynard Keynes.

Amongst the intellectual, practical and experiential skills and considerations Mr Brown applies to the challenges that face the world, is a more radical and philosophical call to action. A call to apply moral and ethical values to these global dilemmas. Moral values are, he says, the basis of that essential life ingredient: hope. Here, perhaps unsurprisingly for the son of a Scottish Presbyterian minister, he cites a verse from the Bible. Of course, he’s also a politician so he balances that biblical reference with words from existentialist Albert Camus. And, if that pincer movement is not enough to win you over, he gives the heads-up to a Gerry and the Pacemakers song: You’ll never walk alone.

This was a tour-de-force from Gordon Brown, entertaining, challenging and uplifting. Exactly what we’ve come to expect from our Friendly Festival in a Walled Town.

The books

RS Thomas’ poetry is available through Bloodaxe Books

The Spy Who Was Left Out In The Cold: The Secret History of Agent Goleniewski by Tim Tate

Seven Ways to Change the World: How to Fix the Most Pressing Problems We Face by Gordon Brown